Protests over everything from water scarcity to pay and living standards have increased pressure on Tehran. Now nuclear talks, which could have delivered an easing of severe US sanctions, have been ‘paused’.

By Andrew England and Najmeh Bozorgmehr

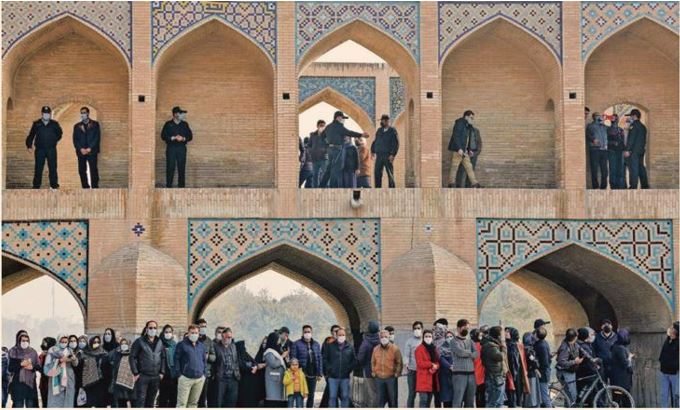

Standing in an arch atop Isfahan’s historic Si-o-Se Pol bridge, Farzad peers down at the water gushing below, recalling how days earlier the river bed was dry and its banks empty of people. “Nobody was here,” says the 18-year-old butcher. “If there’s no water, there’s no atmosphere.”

On this sunny winter’s day, however, the river and its environs are bursting with activity. Behind Farzad, couples pose for selfies while young men dance amid crowds ambling across the 17th-century bridge famed in Iran for its 33 arches. Below, families sit on colourful rugs picnicking along the banks of the Zayandeh Roud.

A combination of drought and poor water management meant the river had not flowed through the city for more than a year. In Isfahan, the status of the Zayandeh Roud — or “life-giving river” in Farsi — is considered by many as a barometer of the mood of the city and the province of 5mn people. In recent months, that mood has been one of frustration — a reminder to the Islamic republic how public anger can quickly spill on to the streets in the nation of 85mn people.

In November, activists in Isfahan and others from the city joined farmers protesting about the lack of water. After the crowds swelled, with some protesters chanting “death to the dictator”, the police moved in with tear gas and rubber bullets to disperse Iran’s biggest ever environmental demonstration.

It didn’t end there. As the water protests stopped, teachers continued their own protests in cities across the republic. Judiciary workers then went on strike in December. Both groups were protesting over pay — the largest demonstrations of their kind by state workers since the 1979 Islamic revolution. Pensioners, sugar industry workers, labourers in the oil sector have all taken part in protests over the past 12 months.

Each outburst of anger underlines just what Tehran is grappling with, from climate change to decaying infrastructure and rising poverty, as it battles to revive its heavily sanctioned economy and keep a lid on simmering discontent.

It was against this backdrop that some Iranians believed regime hardliners, who for years criticised the 2015 nuclear accord — and are ideologically opposed to engagement with the west — may grudgingly accept the need for a deal to unlock the moribund agreement. That would lead to the easing of US sanctions, enabling the republic to export crude oil freely for the first time in almost four years. In return, Tehran, which is enriching uranium close to weapons-grade levels, would have to reverse its nuclear activity to agreed limits.

For weeks, diplomats from all sides were saying indirect talks between Tehran and Washington, brokered by the EU in Vienna, were in their final stages after 11 months of tortuous negotiations. But the talks were “paused” on Friday after Russia, a signatory to the accord and one of Iran’s few strategic partners, threw an unexpected spanner in the works. After the US and Europe imposed sweeping sanctions on Russia in response to Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, Moscow demanded Washington guarantee that its punitive measures do not impede Russian trade with Iran. The fear is that, without Moscow’s co-operation, the talks could unravel.

Even before Moscow’s intervention, both Tehran and Washington had been putting the onus on the other side to take the “political decisions” to get an agreement over the line. Hardliners, who took control of all arms of the state after President Ebrahim Raisi won elections in June, insist Tehran will not sign a deal unless it meets all their demands. They argue that a “resistance economy” has proven it can prevail under the world’s severest sanctions regime and that they can maintain social stability, with or without a deal.

“Sanctions create restrictions, but they cannot block all paths to development,” says Mohammad Nour Salehi, head of Isfahan’s city council. “The sanctions have not ended our activities and this is what the US and their allies have noticed.”

Yet Tehran has been forced to freeze many longer-term development plans to tackle issues such as the water shortages, and a number of the protests over the past four and a half years suggest a clear correlation between economic pressure and social unrest.

In a rare admission of Tehran’s concern, Taghi Rostamvandi, Iran’s deputy interior minister for social affairs, said in January that some social indicators were “worrying”, including the willingness of people to move around the country to join protests.

“In recent years, people’s tolerance has decreased in correlation with rising economic pressure,” he told a government conference. “The alarm bells should ring for us if people think a secular or non-religious state might be more able to deal with the challenges than the Islamic state.”

‘The people of protests’

While the economy has displayed resilience, it contracted by more than 6 per cent in consecutive years, according to the IMF, after former US president Donald Trump unilaterally withdrew from the nuclear accord in 2018 and imposed hundreds of sanctions on the republic. The rial plummeted, causing inflation to soar above 40 per cent. Private sector companies slashed jobs and it is estimated that losses of income during the coronavirus pandemic, combined with rising living costs, could push the poverty rate — defined as living on less than $5.50 a day — up 20 percentage points, according to the World Bank.

External opponents of the republic — there is no organised internal opposition — have capitalised on the protests to suggest the regime’s days are numbered. But Iranian analysts say its grip over the nation is not in jeopardy. After 43 years in power, the republic is confident it has learnt how to manage unrest — choosing when to stand back and allow people to vent; when to make concessions; and when to deploy the security apparatus to crush dissent.

“If you see there aren’t strikes or protests in a country, that’s a bad sign,” says a regime insider, suggesting the demonstrations are more irritant than threat. “It’s not a bad sign if people peacefully complain about the government or demand better standards of living.”

Some analysts say the protests provide a relief valve, as well as an opportunity for the Revolutionary Guards — the dominant security force of the regime — to display their power when needed. Yet they add that what is worrying for a system built on the ideals of revolution and Shia Islam is the frequency and diversity of the protests, even in traditional conservative strongholds.

“They must know that conservatives who supported the revolution, and who they could rely on, are [now] turning into the people of protests,” says Mehdi Moghaddari, an Isfahan-based activist. “It’s not the end [of the protests], it’s a fire under the ash.”

This year’s model

Isfahan has become a prime example. Iran’s third-largest city has been viewed as a bastion of support for the republic since the revolution. Many former and current senior officials, including the judiciary chief, trace their roots to Isfahan province, which is also considered a traditional base for the clergy.

“Whatever happens in Iran,” says Moghaddari, “there’s one foot in Isfahan.” Yet, some in the province feel increasingly marginalised, he adds.

Behzad Haghpanah, a human-rights activist, adds that gradual social changes that have crept across the republic over the past decade, widening the gap between the ageing theocratic rulers that run the country and many younger Iranians, have also played a role in shifting the mindset.

“If you came to Isfahan 30 years ago, almost all women wore the chador . . . now most of the women don’t,” he says. “The rate of divorce has gone up and many women want more freedom — 60 per cent of women go to university in Isfahan.”

But, says Moghaddari, “the biggest thing is water. Isfahanis believe sanctions have nothing to do with the water problem — it’s about mismanagement.”

The November water protests began when hundreds of farmers took to the streets to pressure the authorities to act as their land lay barren for months.

Hossein Vahida, a farmers’ representative, says some 80 per cent of those working the land in the province who rely on the river for irrigation “did nothing last year”. Some tried to find work in the city, others relied on government compensation, but it was “little”, he says, sitting in his home on the outskirts of Isfahan.

Vahida insists the 17-day protest by farmers, traditional supporters of the republic, was non-political. But he admits they were worried that others would exploit the action and says some were rattled by the scale of the protests. “It was a big decision to protest; it was spontaneous, not planned. Next time we will think twice,” he adds.

It was the fear of anti-regime protesters joining the farmers that worried the authorities, says Fazlollah Salavati, a pro-reform political activist and veteran of the 1979 revolution.

“At first it was not a big deal, then it became a security issue as more people joined and there were big crowds,” he says. “The government felt threatened and worried that the crowds could spill over into the city and other places, so the protesters were dealt with.”

The authorities finally opened the sluice gates in February to allow the Zayandeh Roud to flow for 10 days through Isfahan and provide irrigation for crops. But even as Farzad and others on the bridge enjoyed the river’s brief revival, frustration lingered close to the surface, knowing it would be fleeting.

“We blame those sitting up there [in power],” Farzad says, “they were negligent.” The next day the sluices were closed, as Farzad had predicted.

‘Institutions are in crisis’

Officials in Isfahan acknowledge the social and economic pressures in their city, blaming sanctions, which, coupled with the coronavirus pandemic, decimated the area’s tourism sector, as well as drought and climate change. However, they accept that poor management of the water resources is also to blame.

Mehdi Toghyani, a conservative MP in Isfahan, remembers the river running permanently through the city when he was a teenager. Over the past two decades its levels have been falling partly because of changing rainfall patterns but also urbanisation — the city’s population has quadrupled from 500,000 at the time of the revolution to 2mn — as industry and agriculture in the provinces in Iran’s central plateau draw on the Zayandeh Roud’s waters.

“We haven’t done water consumption optimisation, on the contrary we suffer from overconsumption,” Toghyani says.

He blames “various governments”, but believes the protests will force “officials in Tehran to make it a priority”.

He goes on to list other issues that are adding to the pressures in Isfahan, including graduate unemployment and the flight to the cities. “The high level of education doesn’t match the jobs. Isfahan has industry and agriculture, and they need workers not graduates,” Toghyani says. “We have to adapt to the [social and economic] changes.” Such sentiments could be true across the republic. In recent years, there have been protests in Khuzestan, Fars, Alborz and Tehran provinces.

Political disillusionment is also a factor. At the 2021 presidential election, just 48.8 per cent of registered voters bothered to cast ballots — the lowest turnout at a presidential poll since the revolution in what was widely interpreted as a “protest” against the regime.

In Isfahan city, where turnout was 34.6 per cent, Haghpanah, the activist, says it all points to a “crisis in the system in Iran and Isfahan”.

“It’s a symptom that people don’t believe in the system,” he adds.

Mohammad Khatami, a former president and leader of reformists loyal to the republic, warned in February, that the disintegration of traditional family values, the economy, morals and even religion were “more worrisome now than the collapse of the ruling state”.

“The most fundamental institutions are in crisis — if they have not already fallen apart,” he told reformists.

All this is happening at a sensitive time for the regime’s leadership as Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the 82-year-old supreme leader, hopes to lay the foundations for an orderly succession upon his eventual death.

Iranian analysts believe he backed his protégé, Raisi, in the 2021 election partly to end infighting within the system, which loyalists blame for state inefficiency, and to create a more cohesive regime while strengthening the influence of the Revolutionary Guards.

“The country definitely needs to be calm during the transition,” says Saeed Laylaz, an Iranian analyst. He believes most Iranians would prefer a peaceful transition but, if there was unrest, the “guards can hold the country together”.

If US sanctions are lifted, economic relief for the government could be swift, as Tehran would be able to access tens of billions of petrodollars trapped in foreign central banks and rapidly increase oil exports. After the nuclear accord was implemented in 2016, Iran’s crude sales — currently estimated at about 1mn barrels a day — almost doubled to more than 2mn b/d and economic growth rebounded from a deep recession.

“Raisi definitely wants to have a nuclear deal to deliver on his economic promises more quickly and keep the country calm,” Laylaz says.

Yet critics question whether, even if a deal is struck, that would be enough to improve living standards and keep a lid on discontent. “If sanctions are lifted it can make a difference, but not a big difference, because these leaders cannot lead,” says a political activist. “They are not qualified for the 21st century, they belong to the 19th century, so the crisis will continue.”

‘They must know that conservatives who supported the revolution are [now] turning into the people of protests. It’s not the end [of the protests], it’s a fire under the ash’

80% Of farmers in the Isfahan province rely on water from the Zayandeh Roud

48.8% Of registered voters cast ballots at the presidential election in 2021

Source: ft.com

Posted in

Posted in