Hardliners aiming to take advantage of fury over corruption to take power and keep President Rouhani on a tight leash

by Patrick Wintour Diplomatic editor

“They’ve been stealing the money. Cut off their hands, make them pay and answer,” shouted an elderly woman in a black chador, suddenly standing up at a conservative election rally in south Tehran.

Mohammad Hosseini, Iran’s minister for culture and Islamic guidance from 2009 to 2013 under the then president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, replied. If elected, he said, he would always be available to his people. He even read out his phone number to the crowd to underline his sincerity.

Popular anger at corruption, the slide in living standards and the political mistakes of the reformist government of President Hassan Rouhani is widespread in Iran, and fuels the conservatives’ call for “a strong parliament” to be elected this Friday in nationwide elections.

If the conservatives can take power, and appoint someone such as the former Tehran mayor Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf as speaker, Rouhani can be kept on a tight leash in his final year of office before fresh presidential elections.

The deeper question is whether the disillusionment about Rouhani masks a deeper fatalism and disenchantment with all formal politics in Iran.

Despite a Motown-style singing quartet, occasional chants of “death to America and death to Israel”, the crowd at Hosseini’s election meeting, divided by gender and leaning towards the age of 60 rather than 16, did not look that animated. The modern cinema hall was only half full on a Monday afternoon, and even the offer of delicious cream doughnuts had not lured that many from a working-class district of Tehran. At the close of the two-hour event, a hundred or so gathered on stage to wave small Iranian flags and confirm it was their patriotic duty to vote. Hosseini argued “we need a strong parliament to hold Rouhani to account”.

At times the speakers were close to beseeching the audience to each bring a further 100 people to the polling booths this week. The tone reflected the conservatives’ great fear in these elections – that they will win with what one senior Iranian diplomatic official privately predicted would be a landslide, but the success will be soured by mass abstention.

If turnout is low, the conservatives will regain the parliament since its base will come out to vote, but if it is too low the result could be taken as a vote of no confidence in the whole Islamic Republic. One survey shows 75% do not plan to vote, and in the elegant squares of the University of Tehran, small groups gathered calling for a boycott, holding placards saying: “The people are fighting poverty, the regime is looking for votes.”

One reformist candidate, Vahid Tootoonch, said “it is a freezing cold atmosphere in Tehran towards the elections”, and that at best he hoped for a vote around the 40% mark.

Yet predictions in such a complex, multi-layered society as Iran are foolish, especially since it has been through some of the most turbulent months in its 41-year history. Hundreds were killed in riots caused by “shock therapy” fuel price rises in November. The government declined this week to give an official figure on the deaths.

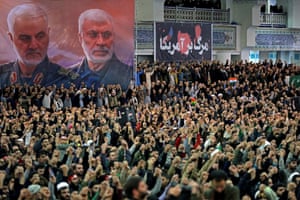

Then Donald Trump’s assassination of the head of Iran’s elite al-Quds force Qassem Suleimani – his picture adorns every highway in Tehran – reunited the country, only for Iranian military reprisals, leading to the mistaken downing of a Ukrainian civilian jet, reignited society’s divisions. One disillusioned reformist activist said: “The regime’s cover-up over the jet was the last straw for me. Iran’s politics is a game. If the roots of a tree are poisoned, it does not matter how you decorate the leaves. I am done with it.”

Meanwhile the pressure on the economy, due to American sanctions as well as corruption, is relentless. On Tuesday morning around Ferdowsi Square in Tehran the hundreds of currency exchange markets, which have proliferated since sanctions were imposed, bustled with customers. Overnight, the markets had pushed the value of the dollar up a further 10%, amid concern that Iran is set to be blacklisted again by the international Financial Action Task Force after failing to comply with a final warning to sign up to its money-laundering and anti-terror laws.

Blacklisting would cut Iranian banks off further from the world financial system. Abdolnaser Hemmati, the governor of the Iranian Central Bank, insisted the risk of being blacklisted was low, but the steady flow of taxis turning up to the exchange markets showed many were unconvinced. At times $10,000 in cash were being bought and sold.

The siege backdrop could not make for a greater contrast than the last parliamentary elections five years ago when Rouhani’s reformists, promising to take the country out of economic isolation, became the largest party, winning all 30 seats in Tehran. Then the possibility of change gripped the capital.

Now, at a thinly attended meeting for a reformist faction linked to the former president Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, held in a backroom, the panel were peppered with questions about their record and whether their support for the nuclear deal had been mistaken. Tootoonch doggedly defended the deal, saying it was a model for showing negotiations can have results, but he said no one could have foreseen that Donald Trump would be elected US president or Iran’s conservatives would resist the deal as much as they did.

By contrast, Mohammad Sadegh Kooshki, a hardline academic at Tehran University, said he had always predicted the nuclear deal would not bear fruit. “We never held a tool to force the Americans to hold to their commitments. The Americans had a tool in sanctions. We did not, and as a result we have lost six years developing our nuclear power plants.”

The truth was that neither the US nor Europe dared allow a truly powerful independent industrial country to be formed in the Middle East’s heartland, he said. “The Americans want us to be oil salesmen, just buying goods from them like the Saudis, and Emiratis. Big powers don’t want to have rivals,” he said. He favoured building relations with China or Russia.

At the barracks-like and conservative Shahed University on the south side of Tehran, Dr Hamidreza Sayyedi was equally insistent Iran would survive. He said the religious nature of the regime was fundamental to its sustainability: “If England had suffered 1% of the level of sanctions that we have suffered, the country would have collapsed. We can endure.”

The Islamic Republic was not some medieval merger of church and state, but a newer, higher form of governance, he said.

But the question then arises that if the conservatives are so confident the tide is with them, why had the 12-strong Guardian Council composed of clerics and jurists largely appointed by Ayatollah Ali Khamenei banned so many reformists from standing in the elections?

More than half the 14,000 applications to stand have been rejected for various reasons, such as a lack of true Islamic faith, or good health. But it is not the mass nature of the disqualifications that matter, but their targeted nature. Credible figures such as Ali Motahari, Mahmoud Sadeghi, and Shahindokht Molaverdi, all critics of various forms of state repression, have found themselves debarred. Even Rouhani complained in public and private that elections without contests were appointments, not democracy.

The political engineering has meant the reformist umbrella group decided not to put forward a unified list for the 30 seats reserved for Tehran in the 290-strong parliament. But it left others to decide if they wished to put up lists, and did not advocate a boycott, a halfway house that dissatisfied some.

The heavy-handedness of the intervention suggests Khamenei sees the reformists’ disarray as a chance to consolidate his power ahead of the presidential election next year, and even prepare his succession.

At an hour-long press conference on Wednesday a spokesman for the Guardian Council repeatedly denied claims he had rigged the elections, saying the candidate qualifications decisions were based on the law, asserting the Council was “not a political club”.

He said turnout in elections in Iran had never fallen below 50%, but if it did that was no problem, pointing that the figure was similar to some French elections.

Mohsen Aref, a one-time campaigner for Rouhani at Allameh Tabataba’i University in Tehran, argues Rouhani’s failure has revealed the impossibility of reforming the regime.

He said Tehran only revealed its truths slowly, and the real truth is that most Iranians are not religious hardliners, but highly educated people with a rich culture. “We want to engage with the world. Iran started as a totalitarian majority regime. It is now a totalitarian minority regime.” Turnout, as much as the result, will help reveal if he is right.

Posted in

Posted in