by Liberation|Published August 19, 2022

by Steve Bishop

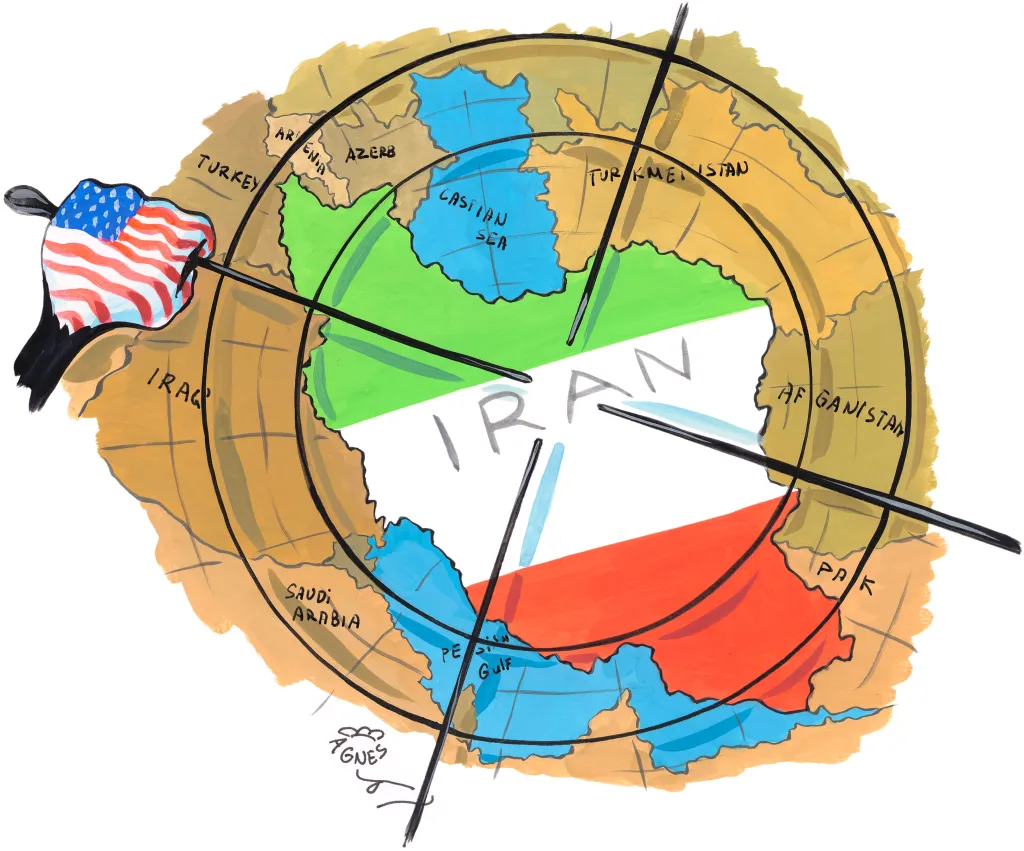

The situation in the Middle East is never far from the news headlines. In recent months that has meant a renewed focus on the Iran nuclear deal, including a debate in the House of Commons at the end of June this year. Steve Bishop assesses the prospects for a new agreement with Iran and the implications of failure to reach a deal.

The House of Commons debate on 30 June this year, on Iran’s nuclear deal, was opened by Robert Jenrick MP and set the terms of the debate in the context of Iran’s potential to develop nuclear weapons and what Jenrick referred to as Iran’s “other destabilising activities in the region”.

Earlier in June, the UK, Germany, and France had released a joint statement saying that they were ready to conclude a deal with Iran. That would have restored the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the basis of the Iran nuclear deal which held until May 2018, when the United States unilaterally walked away from the agreement. Following the statement by the European powers, it was revealed that indirect talks between the United States and Iran had resumed in Doha, Qatar.

By mid-August, reports were circulating that a final text had been agreed. Tehran has indicated that, from its perspective, progress has been made but there are still outstanding details to be finalised. There is a sticking point for Tehran on the status of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), which the US regards as a terrorist organisation. Tehran also wants guarantees that any agreement will be binding on future US administrations, so the deal cannot be reneged on as it was in 2018 by President Trump.

It is unlikely that either of these positions will be palatable to Washington. Some observers also see a final agreement as being unlikely given Iran’s increasingly close co-operation with both Russia and China. Recent co-operation with Russia in particular, on satellite and weapons technology, has been frowned upon in the West.

The need to reach a deal is widely recognised however as a prerequisite for any chance that Iran may be engaged more positively with the international community. The lifting of sanctions could not only reduce Iran’s uranium enrichment programme, confining it for purely civilian purposes, but also be used as leverage to address the regime’s appalling human rights record. Both issues would send positive messages across the Middle East by reducing the likelihood of conflict and bringing the issue of human rights to the forefront of the debate.

In his contribution to the debate, Jeremy Corbyn MP was very clear that, “Any discussion with Iran must include a discussion of human rights”. However, Corbyn pressed on to widen the debate to consider the issue of peace in the Middle East, in the context of the non-proliferation treaty review conference this August in New York. In this regard, he expressed the view that,

“While I fully appreciate that Iran clearly has developed centrifuges and enriched uranium almost to weapons-grade, two other countries in the region either have nuclear weapons or could. One is Israel, which clearly does have nuclear weapons, and the other is Saudi Arabia, which could quickly develop nuclear weapons if it wanted. The urgency of having a negotiation and a revamped version of the 2015 agreement, or something like it, is important if we are to try to preserve the peace of the region.”

While the issue of peace in the region and the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons was central to Jeremy Corbyn’s argument, other contributions chose to sidestep the issue and focus upon the trustworthiness of the Iranian regime, going so far as to question whether any kind of deal was even possible.

Steve McCabe MP was keen to revert to a more punitive approach with regard to Iran, focussing upon “the malign activities of those who control the Iranian regime” while failing to see the bigger danger of not addressing the issue of nuclear non-proliferation in the wider context of the Middle East.

The activities of the Iranian regime are indeed “malign” as the Committee for the Defence of the Iranian People’s Rights (CODIR) has spent the last 40 years playing a central role in pointing out, while campaigning for peace, human rights, and democracy for the people of Iran.

However, in the context of the geo-political situation in the Middle East, and the increased international uncertainty due to the war in Ukraine, an agreement which could be the beginnings of a more stable region would be worth aiming for.

The situation inside Iran remains finely balanced. The punitive sanctions imposed following the unilateral withdrawal from the 2015 deal by the United States has seen the Iranian economy contract by 6% year on year according to the IMF. Social unrest has been gathering momentum as a result of the impact of sanctions upon the economy. Widespread job losses have plunged many into poverty with inflation running at over 40% according to the World Bank.

Concern with the situation has been expressed by Taghi Rostamvandi, Iran’s deputy interior minister for social affairs, who has observed at a government conference that,

“In recent years, people’s tolerance has decreased in correlation with rising economic pressure. The alarm bells should ring for us if people think a secular or non-religious state might be more able to deal with the challenges rather than the Islamic state.”

Such fears are exacerbated by the fact that Iran’s population is predominantly young, with 45% being under 35-years-old and less wedded to the aims of the Islamic regime than some of their elders. It is from this section of the population that demands for better jobs, educational opportunities, and greater democracy are being heard most vociferously.

The imperative for the regime remains to secure a deal. It is believed if US sanctions are lifted, this will bring some economic relief for the government. Tehran would be able to access tens of billions of petrodollars trapped in foreign central banks and rapidly ramp up oil exports. For recently elected President, Ebrahim Raisi, a nuclear deal is seen to be the opportunity to deliver on economic promises and hopefully keep the country calm.

Some hardliners within the Iranian regime, however, are willing to risk a no deal situation arguing that what they term a “resistance economy” has prevailed, in spite of the severity of the sanctions regime to date, and that they could continue with this while maintaining social stability.

The extent of social discontent in evidence across the country may contradict such an assessment, but the fact that some inside the regime see toughing it out as an option will be of concern to much of the Iranian population. Tehran has been forced to freeze many longer-term development plans to tackle issues such as water shortages, and the number of protests over the past four-and-a-half years suggests a clear correlation between economic pressure and social unrest.

The situation in Ukraine has already had an impact upon the likelihood of a deal being agreed. Talks in Vienna which started in April 2021, aimed at reviving the Iran nuclear deal, were suspended recently when Russia insisted that the US sanctions should not be an impediment to its trade with Iran. The Islamic Republic relies on the import of grain, fertilisers, cooking oil, and meat from Russia, which have been abruptly halted. Ironically, the US and its European allies are attempting to leverage pressure on Iran to step in and provide oil and gas to the West to fill the void in supply from Russia.

There is little doubt that the regime in Iran is under pressure due to the deteriorating economic situation. At the same time the West is under pressure to find some accommodation as a result of its issues with Russia. A revival of some form of the JCPoA may well be expedient for both, while at the same time alleviating some of the pressures of poverty from the people of Iran.

Certainly, any deal should be linked to the wider issue of nuclear non-proliferation in the Middle East, as that really would be a major step forward for peace in the region.

Steve Bishop is a longstanding member of the National Executive Council of the Committee for the Defence of the Iranian People’s Rights (CODIR), member of Liberation, writer, blogger, and regular contributor to Liberation Journal.

Posted in

Posted in