Hardliners strike a defiant tone in public, but behind the scenes there is debate about how to respond to demands for change

Andrew England and Najmeh Bozorgmehr in Tehran YESTERDAY

When the Islamic regime called, hundreds of thousands rallied. In cities across Iran, women, mostly in traditional black chador body cloaks, joined huge crowds of men carrying banners, portraits of supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and national flags to celebrate the 44th anniversary of the 1979 revolution.

The mass gatherings last month offered a chance for the leadership to put on a muscular display of support after months of nationwide protests that presented one of the biggest domestic threats to the republic since its founding.

President Ebrahim Raisi did not let the moment go to waste. In Tehran’s Freedom Square, a flashpoint for the anti-regime demonstrations months earlier, he railed against the republic’s enemies and boasted of the unity of his nation.

“Today’s crowds are sending a message of hopelessness and disappointment to the enemy,” he said, claiming the scale of the gathering was “the victory of the Islamic revolution”.

But the spectre of rebellion was never far away — anti-regime hackers briefly interrupted state television’s web broadcast of Raisi’s speech with a voice shouting: “Death to the Islamic republic.”

The events on that day hint at the state of play in a deeply polarised nation, rife with tension and uncertainty seven months after the death of Mahsa Amini in police custody triggered demonstrations across more than 150 cities and towns.

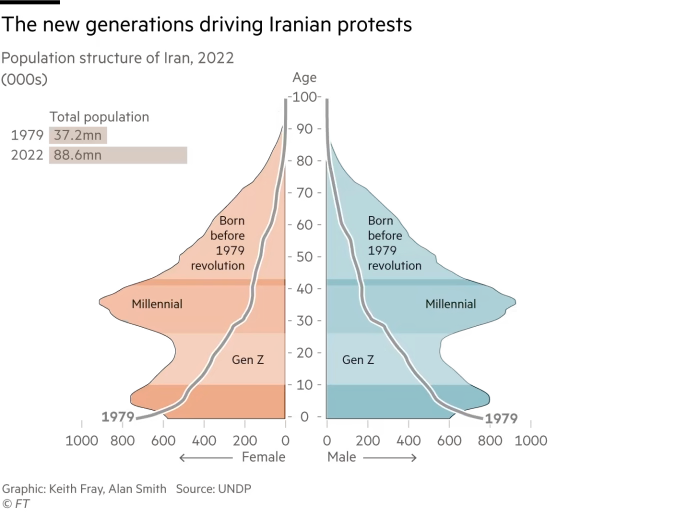

Outwardly, the regime is projecting confidence that it has navigated the tumult. The protests have largely petered out. Regime loyalists have taken a characteristically autocratic and paternalistic approach to explaining away the dissent, suggesting those young men and women who took to the streets simply need to be better educated about the values and ideology of a revolution that took place before most were born.

Yet every day, thousands of women are openly breaking the law and defying one of the most symbolic tenets of the republic by not wearing their compulsory hijab head coverings. From Tehran’s affluent north to its poorer south, on streets, in private offices, shops and cafes, it is an unprecedented display of civil disobedience.

“After what has happened, it’s the least we can do,” says one young waitress in the capital, wearing a simple crisp shirt with black trousers — and no hijab.

Activists and analysts warn that beneath the surface, the anger that inspired the protests is still bubbling away. The republic’s legitimacy, long on the wane, is increasingly spent, they say, with the gap between the ageing theocratic leadership and the aspirations of the youthful population wider than ever.

The question is whether the ideological hardliners who have controlled all spheres of the state since elections two years ago will allow the social, cultural and political changes that analysts believe are their best hope of staving off more unrest.

Or will they turn inwards, impose harsher restrictions, rely on the state’s powerful security apparatus to quash dissent, and risk more protests and violence? Analysts say that would put the future of the republic at stake and threaten 83-year-old Khamenei’s plans for a stable succession.

Signs of a softening

So far, the regime has made some concessions, including turning a blind eye to women not wearing the hijab, despite no official changes to the law.

The morality police, who triggered the crisis after arresting Amini for not wearing her veil properly, have disappeared from the streets. The large, green metal doors guarding the only morality police station in Tehran are closed, a single officer looking out from a watchtower and a poster on the tired, cream walls encouraging people to call a hotline if they have complaints.

Khamenei also pardoned tens of thousands of prisoners days before the revolution anniversary. The judiciary says more than 82,000 were released from prisons or had their sentences reduced, including 22,000 who took part in the protests. The long queues of visitors outside Tehran’s notorious Evin prison during the unrest have disappeared.

Yet the critical issue for many Iranians is whether the leadership will now go further.

Some, including those who protested, believe it is already too late, arguing that the long-held notion that Iranians should put their faith in change from within their unique system has been destroyed after years of voting for pro-reform forces yielded little in the way of political, economic, social or cultural reform.

At the end of the day we can die — Iranian women are not scared of anything anymore

“What has been achieved through the protests is that in people’s minds this ruling system will go and power has been split between the people and the rulers,” says Abdollah Momeni, an activist. “It [the unrest] has not ended; maybe the cycle has ended.”

In an upmarket Tehran shopping mall, two fashionably dressed 16-year-old girls who make no attempt to comply with conservative dress codes for women display a similar defiance.

“At the end of the day we can die — Iranian women are not scared of anything anymore,” says Rojina, who joined the protests with friends. “Everyone should be able to choose. Nothing should be forced on us.”

Accustomed to adversity

The republic has been confronting crises with regularity since its birth. In the 1980s it faced internal battles and fought a devastating eight-year war with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. In 1999 it was the turn of students to vent their fury, a politically and socially important group that played a significant role in the 1979 revolution.

A decade later, millions of people protested for weeks over disputed elections. In 2017 and 2019, it was economic grievances that drove citizens on to the streets, with protests turning violent as mobs burnt state buildings and attacked security forces.

But the most recent unrest was different. The death of Amini while in Tehran’s morality police station sparked an explosion of anger that crossed sect, age and class. Many believed she died after being beaten, dismissing the authorities’ claims that the 22-year-old had a heart attack.

Initially, the outpouring of rage focused on gender rights, with women, students and high school girls like Rojina braving the security forces to demonstrate and publicly burn their hijabs. But the protests rapidly morphed into the most sustained and determined calls for regime change the republic has yet endured, including demands for the introduction of a secular democracy, just as the authorities were grappling with a moribund economy and escalating tensions with the west.

“It was where the economic, social and religious crises converged at one point,” says Momeni, who spent five years in prison after being arrested in the wake of the disputed 2009 election.

The rattled regime responded with batons, birdshot and tear gas. More than 300 people were killed, including dozens of children, according to Amnesty International, and tens of thousands were detained. Four men were executed.

Yet hardliners take solace in the fact that it was mainly those from the middle class who protested, not the poorer segments of Iran’s population most affected by the nation’s economic malaise.

Pro-reform Iranian analysts estimate up to two million people took part in protests, but Hamidreza Taraghi, an influential hardliner and a senior official at the Imam Khomeini Relief Foundation, the state’s biggest charity, says drone surveillance put the numbers at “around 500,000”. He describes most of them as “the youth who were deceived through social media”.

Asked what lessons the regime learnt from the protests, Taraghi is uncompromising, questioning “why should we abandon the demands of [those who celebrated the revolution anniversary] to the 2-3 per cent of the population”?

“We got to better understand our weak and strong points. One of our weak points was freeing up social media, which happened under the previous [more centrist] government,” he adds.

“Our education system should be able to train the youth . . . in line with the causes of the revolution,” Taraghi says. “It has to become more Islamic and more patriotic, the youth should love the national flag”.

Other prominent conservatives take a similar view. Hossein Shariatmadari, the editor of the state-controlled Kayhan newspaper, a mouthpiece for hardliners, oscillates between likening “rioters” to terrorists and describing protesters as misled youth.

He is unhappy that women are abandoning the hijab. “It’s not the right thing, they are breaking the law. Gradually, they can be made aware of this, but the way to deal with them is not to arrest them, it’s to increase awareness,” Shariatmadari says. “Next year, if you come here you will not see this.”

“If the revolution becomes weak, it’s when people give up on Islam — that’s impossible,” he adds.

‘Power in people’s hearts’

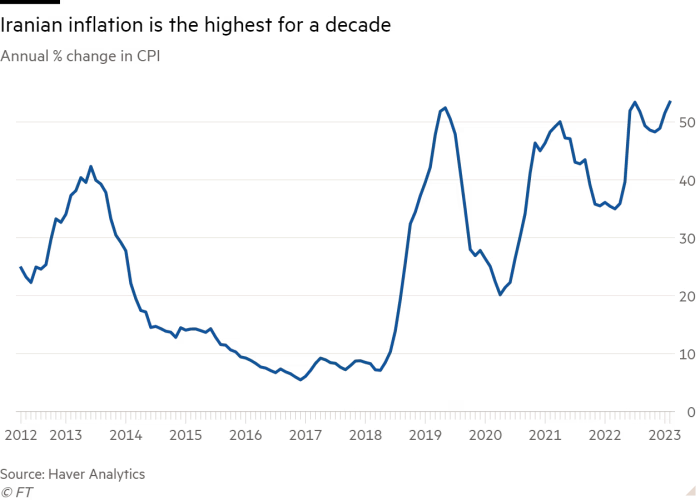

Others suggest that despite the uncompromising response in public, there has been debate within hardline circles about the way forward as the authorities grapple with social pressures and economic turmoil. Inflation is running at 53 per cent, while the rial has lost half of its value against the dollar since Raisi took office in August 2021.

“They are talking every day; we are talking to them. They are very angry with each other,” says Saeed Laylaz, a Tehran-based analyst regarded as loyal to the regime but with a reformist bent. “Some say they haven’t been tough enough; others argue they should be less tough on the cultural aspects because the regime is not able to manage the economy.”

Hints of the internal debates have surfaced in speeches and the local media, with some conservative politicians making the case for some social and cultural change.

Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, the hardline parliamentary Speaker, said in January that the regime’s “power is not that of hard and absolute power, which has limited use for a limited period. Our soft power is [what’s] in people’s hearts”.

Fuelling speculation that he opposes the regime’s tightening restrictions on social media, he added, “if the revolution is unable to have a [strong] presence in social media, sooner or later we will be marginalised”.

Ali Larijani, another prominent conservative, questions the focus on the hijab. “At a time when people are struggling with economic hardship, suddenly the issue of hijab is highlighted in an untimely manner and incorrect approach,” he told a conservative newspaper in October. “The question is, should the state interfere in all affairs? Where should it stop?”

Ezzatollah Zarghami, the conservative tourism minister, delivered his own unique message to conservative men worried about women not covering their hair: “If you feel aroused, don’t look!”

What next?

Shariatmadari, the Kayhan editor, says debate is normal but pushes back against the notion that there will be significant concessions to protesters and secularists.

“If you close the door for dialogue, the Islamic republic will face problems, but did anyone [in the system] support the protests? No,” he says. “It’s so natural that something happens inside a family and you try to find out what happened. This does not mean we compromise on principles.”

Khamenei, the ultimate decision maker, has shown few signs that he is about to change course. In a speech last week, the supreme leader conceded there were “weak points” inside the ruling system and society that needed to be addressed. But he said demands for changes to the political system were part of an enemy conspiracy designed to make the republic submissive to the west.

The highest cleric was a focal point for the protesters’ ire. Many Iranians suspect he was behind the election of Raisi and the formation of the most hardline government in a decade, after all credible reformist and centrist candidates were barred from contesting the poll.

Analysts believe Khamenei’s strategy was to try to put an end to the internal clashes that dogged previous governments and smooth the path to a succession. In practice, it meant further empowering the most hardline factions of the regime.

Raisi, a Khamenei protégé and potential successor, duly took power, but at a significant cost to the republic’s claims to popular legitimacy. The seemingly preordained nature of the poll crushed any lingering hopes that the system would countenance reform from within and the 48.8 per cent turnout — the lowest at a presidential election since 1979 — was viewed as an indictment of the regime’s increasing unpopularity.

Hamid-Reza Jalaeipour, a sociologist, says how the authorities behave ahead of next year’s parliamentary elections will be one of the indicators about which direction the leadership takes.

“Before the last election they thought whatever they did, people had no choice but to accept. But they realised the population will come out and shout and criticise,” he says. “Those who hold power are two groups, some are more moderate and want to show flexibility, others are radical. We have to see which group gains the upper hand.”

Some reformist politicians, still loyal to the Islamic system despite their own reservations, cling to the hope that those in power have little choice but to allow changes in order to maintain stability.

“Many may be surprised, but what happened really paved the way for reform inside society and the political system,” says Mohammad Ali Abtahi, a cleric and former reformist vice-president. But, he adds, the leadership is wary of making public pronouncements for fear of appearing weak.

“It would mean they are following in the footsteps of the [last] shah,” Abtahi says. “He reformed and it emboldened the opposition forces to take power.”

However, when asked if he still believes change can come from within, Abtahi struggles. “We also don’t believe it’s possible . . . but we don’t believe in anything else,” he says. “We are stuck behind a big rock.”

If they cannot accept a revolution from the top, they will witness a revolution from the bottom

Momeni began losing faith in the notion of change from within years ago. Reforms, he says, are now seen as a means of keeping the “silent majority” off the streets without delivering any genuine change.

“If the regime wants to get out of this cycle, it must impose a revolution from the top by taking such measures as removing the government, dissolving parliament, forging relations with the west and allowing social freedoms,” he says. “That would be like suicide, nothing would remain of the Islamic republic. But if they cannot accept a revolution from the top, they will witness a revolution from the bottom.”

Others say the lack of an obvious or credible alternative, as well as the bloodshed and chaos that has engulfed countries such as Iraq and Syria, make many Iranians wary of risking greater instability.

“I still believe that the majority of people think that if it’s a choice between the collapse of the Islamic republic and its survival, they prefer its survival,” says Abtahi. “It’s definitely not that they love it, they are scared of an uncertain future.”

Back in the mall, Rojina and her friends discuss their hopes for the future. She wants regime change. Sayeh, also 16, wants “freedom,” while Aryan, 18, simply says he craves a decent lifestyle — and advocates patience.

“If we want to achieve something we have to pay the cost. I’m sure the things we want aren’t going to happen easily,” Aryan says. “It will happen when I’m a father and go to the street with my son.”

ft.com

Posted in

Posted in