Madrid – JAN 15, 2025 – 06:24 CST

He had only two hours to decide: exile or prison? “The secret service was interrogating the film crew, and on top of that, the Islamic Revolutionary Court announced that day that within a week, they would carry out the sentence condemning me to eight years in prison, plus a flogging and confiscation of my property,” recalls Iranian filmmaker Mohammad Rasoulof.

For years, Rasoulof, 52, had been one of the most outspoken critics of the Ayatollah regime, so much so that he was convicted of “intending to commit crimes against the security of the country.” This marked the end of a long journey of opposing the government, along with multiple stints in prison and house arrest.

With his family safe, Rasoulof said goodbye to his plants (“my most prized possession”), looked out at the mountains from his Tehran window, asked a friend for money, left all his electronic devices behind to avoid being traced, and contacted a member of a network he had met in prison that helps persecuted individuals escape the country. “I went into exile, something I had never even considered.”

Rasoulof knew from the outset of filming The Seed of the Sacred Fig that he was sabotaging his life in Iran. Sitting in the cafeteria of the Maria Cristina hotel in September during the San Sebastián Film Festival, where the film was presented in the Perlak section, his story took on a bittersweet tone. He arrived in Hamburg on May 10, 28 days after fleeing Tehran. He had studied film in Germany as a young man, and his daughter, the actress Baran Rasoulof, lives there.

Since then, he has left Germany several times. At the end of May, he appeared at Cannes, where his film closed the competition and won a special mention from the jury. In September, he presented the drama at the San Sebastián Film Festival, and he traveled to the New York and Busan (South Korea) festivals in November. He was also in Los Angeles during the Golden Globes ceremony. The Seed of the Sacred Fig is representing Germany at the Oscars, as it is a co-production. Rasoulof emphasizes the importance of his editor, Andrew Bird, a British expatriate living in Germany, to the film’s outcome and to his personal life. “As I was filming, I was sending him the material because I knew it would be safe with him,” he says.

Although he has never sought to assume the role of a political spokesperson, Rasoulof has faced numerous hardships due to his commitment. He was arrested in 2010 for filming a movie about the Green Movement (the protests following the 2009 presidential elections), which he never finished. And in 2021, he was placed under house arrest in 2021. During the promotion of his previous film, There Is No Evil, which won the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival, he had to participate in the event via video call from a back room of his home in Shiraz.

In 2022, he was sent to prison for seven months after signing a critical petition against the government. While incarcerated, he met another Berlinale-winning filmmaker, Jafar Panahi, and together they listened to the stories of how women formed the Women, Life, Freedom movement after the police murder of Zhina Mahsa Amini, who had been arrested for not wearing her hijab correctly. This led to a widespread uprising against the oppression of the regime.

“Two curious things happened to me in prison,” Rasoulof recalls. “One was that I discovered the jailers were watching pirated copies of There Is No Evil. The other was when one of the interrogators gave me a pen and told me that every time he entered prison and heard the door close, he remembered his children’s questions about what he did.”

This is how The Seed of the Sacred Fig was born. The film begins as a family drama, with the family celebrating the father’s promotion at work, where he’s appointed as a judicial investigator, a step toward potentially becoming a judge. But then the wave of protests following Amini’s death erupts, and the wife and two daughters begin questioning the world around them. The spiral of violence reaches their home when one of the girls’ friends is brutally beaten. Meanwhile, what is the father doing at work? Why is he not answering his phone? At this point, the film shifts into a state of terror.

The filmmaker explains that he knew from the beginning that he was tightening the government’s grip on him. In his previous films, he had conveyed political and social messages, and he was aware he was being watched. He even grew a beard for the filming of There Is No Evil so no one would recognize him during the outdoor shoots.

“I didn’t go near the street scenes for The Seed of the Sacred Fig to avoid drawing attention. In fact, many passers-by and even the police thought it was a government film and didn’t bother me,” he smiles.

At the end of the shoot, the sentence was handed down. “I asked my lawyers how much time we would gain if we appealed, and they told me that with the Muslim New Year festivities and the usual bureaucratic delays, two months would pass — just enough time to finish the film,” he explains.

In The Seed of the Sacred Fig, Rasoulof reflects on how, despite widespread protests, the ayatollahs remain in power: “Dictatorial systems succeed and are maintained over time not because of the leaders, but because of the middle management who carry out and often amplify their orders. The regime is using religion as a political tool, and my films focus on this indoctrination. The Islamic Republic is a dictatorship that has taken Iranians hostage; repression is its essence. Any announcement of change is just propaganda.” Is he in danger himself? “If they can, they will eliminate any opponent, but I don’t spend a second of my life thinking about it.”

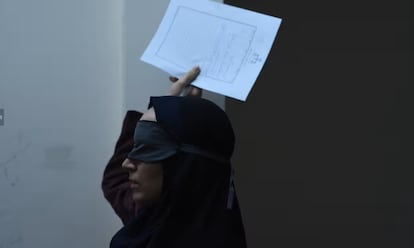

For the first time, women take center stage in Rasoulof’s film. “They are the ones who are keeping the fight for freedom alive, the ones who inspire the rest of us. I’m under no illusion: the battle for human rights in Iran is almost entirely in the hands of women. Soheila Golestani, who plays the mother, was imprisoned for 12 days in November 2022 after posting a protest video in which she appeared without a veil. Only the actresses who play the daughters could accompany me to Cannes, as the passports of the rest of the cast and crew were withheld.”

For years, Rasoulof was highly critical of the more passive filmmakers, particularly singling out two-time Oscar winner Asghar Farhadi for his timid comments on the repression in Iran. “After the women’s rebellion, many artists, actresses, actors, and directors stopped being ambiguous. The question became clear: do you support the values of this system or not? I saw this shift even in my own case; I thought I would struggle to find actors for the film, but the opposite happened: there were plenty of volunteers.”

And now what? “I still feel a bit lost outside Iran. I am from the south, very much my homeland. I never wanted to consider exile. But when I was sentenced, I sensed that sooner or later I would have to face it. Staying meant accepting censorship or becoming a filmmaker-victim. However, I only left when I knew I could continue creating abroad. If there were no possibilities to make more films, I would not have left. But sooner or later, I will return.”

Posted in

Posted in